Imagine this: the government shuts down your play the morning after opening night! What do you do? If you’re Victor Hugo, that’s easy: you go to court—and you argue your own case for freedom of speech.

Hugo’s play Le Roi s’amuse—The King Has a Good Time—took him to court twice, in fact. First he protested the government minister’s actions. Then, 25 years later, he argued to get deserved royalties from Rigoletto. After all, he’d written the original play.

Let me tell you how that all happened—and how the play’s themes touch on Hugo’s life and ideals. And—I think you’ll agree—on ours.

In 1832, Victor Hugo had a lot at stake. First, his principles—because for Hugo artistic freedom and free speech were one and the same thing. By fighting for the right to stage his plays, he believed, he was helping everyone maintain personal liberties—which was an ongoing struggle in the face of increasingly restrictive monarchies. In addition, as the acknowledged French Romantic leader, Hugo needed to support the fledging Romantic theatre movement. Finally, personally, and on a practical front, Hugo had his wife and four beloved children to provide for. Theater was the best way to make a living as a French writer in the 1830s. Poetry may have launched his career—but poetry alone would not put enough food on the table.

Hugo was a poet through and through. When he was only 17, one of his poems won a national award. He published several poetry volumes in his early 20s. So it wasn’t too big a surprise when he was selected to be the official poet at King Charles X’s coronation ceremony. Hugo was then 25 years old, and he was about to write the manifesto for French Romantic theater and put his poetry on stage.

Romantic manifesto:

That manifesto came in the long preface to his play Cromwell. There Hugo argued that it was illogical and unnatural to separate theater into tragedy and comedy, as the French Classicists had done in the 1600s. As much as he admired Molière and Corneille, Hugo admired Shakespeare more. Theater should reflect life. People’s actual language belonged on the stage. In the end, Hugo pointed out, life is drama. It’s a mix of tragedy and comedy, an intertwining of the sublime—which had been claimed by authors of tragedies—and the grotesque—which were things comic or horrible. He argued implicitly for the sort of excess that can come from passion, the deep feelings we find in the character of Rigoletto.

But his play Cromwell was so long and complex that it was never staged during Hugo’s lifetime. And his next play, Marion de Lorme, was blocked from the stage. Even though the play was set two centuries earlier, the censors saw in the king’s weakness an allusion to King Charles X. As recompense for shutting down the performances, the government increased Hugo’s royal subvention by 4,000 francs. But Hugo spurned that money in a public letter, writing, “I had asked for my play to be performed—and I ask for nothing else.”

Still, Hugo had learned a lesson. He set his next play in sixteenth-century Spain—far enough away from the French monarchy to avoid censorship for political reasons, at least. With that play, Hernani, Hugo opened up Parisian theaters to Romanticism. You opera buffs may well recognize Hernani as Giuseppe Verdi’s Ernani, another of his operas based on a Hugo play.

Hernani :

Hernani was performed at the historic Théâtre-Français—which is today the Comédie Française. Dating back to Molière and the 17th century, it’s considered to be the world’s oldest still-active theatre. It was in 1830 the bastion of French Classical theatre.

During the opening night of Hernani and the following few weeks, Hugo’s fellow Romantics packed the theater. They cheered his dramatic moments and rule-breaking poetry. Many of Hugo’s lines shocked the traditional audience members who were used to the limited, euphemistic Classical vocabulary. The Romantics often drowned out boos from the bourgeois Classicists. Hernani’s success ended the two centuries’ long domination by French Classical theater—with all its rules about time and theme and place.

Hugo shocked people, too, by making his hero an outlaw bandit. By doing so, he maintained his focus on people on the edge of—or even outside—society—outcasts who nonetheless have a deep capacity for love. The previous year, for example, he had given us the hunchbacked bell ringer, Quasimodo, in his novel Notre-Dame de Paris, a young man who sacrifices himself for love. A few years later Hugo would create one of his most famous social outcasts, ex-convict Jean Valjean in Les Misérables.

Le Roi s’amuse :

In Le Roi s’amuse, Hugo’s protagonist lives on the edge of noble society, as the king’s hunchbacked court jester—or fool. Named Triboulet in Hugo’s story and Rigoletto in Verdi’s, he does not hesitate to comment on the society he observes. Those comments get him—and Hugo—into trouble.

Hugo based Triboulet on the real jester in the court of King François Ier. But Triboulet is a model Romantic character. He is both physically grotesque—like Quasimodo—and spiritually grotesque in his malevolence and plotting. At the same time, though, he is sublime in his deep love for his daughter, Blanche—Gilda in Rigoletto. So extreme that he is sometimes melodramatic, Triboulet is nevertheless moving in his all-encompassing love for his daughter and his agony over losing her.

That’s one place in which this play touches closely on Hugo’s life. Hugo loved his own children with similar intensity—especially his eldest daughter, Léopoldine. Hugo, of course, didn’t know it when he wrote Le Roi s’amuse, but 11 years later Léopoldine would die in a tragic boating accident. Hugo wrote some of his most magnificent poetry about his grief over losing his daughter, and we hear echoes there of Triboulet’s anguish over his daughter’s death.

Similarly, Jean Valjean’s all-encompassing love for his adopted daughter Cosette reminds us of Triboulet’s. Triboulet in Act II tells Blanche that she is all he has. She is—just as Cosette is to Valjean—“My city, my country, my family, my wife, my mother, and my sister and my daughter, my happiness, my riches, my religion, and my law.”

Opening night:

Hugo wrote Le Roi s’amuse in a record 17 days, averaging 100 lines of poetry per day. Opening night was much like the Battle of Hernani had been 2 ½ years earlier. Despite the Théâtre-Français director’s efforts to control the situation, the partisans of the Romantic aesthetic continued their fight for modern theater.

Everyone was there on November 22, 1832: musicians, painters, poets, novelists, playwrights, actors, journalists, magazine editors. People such as Balzac, Stendhal, Musset, Nerval. People from the financial world, politics, the head of the Paris police, and half the literary French Academy—which Hugo yearned to be invited to join. As the play proceeded, boisterous conflicts broke out between the conservative audience members and the enthusiastic young Romantics, much as they had during Hernani.

But the outcome was not as good for Hugo. Rehearsals of the play had not gone well. So, when the Classicists booed some of the more out-there lines, some actors became flustered. They even began to forget some lines, and the play made less and less sense.

Le Roi s’amuse bombed with the public and with the critics. It was “the Waterloo of Romanticism,” wrote one journalist two days later. It was, Hugo’s biographer Jean-Marc Hovasse tells us, a humiliating public catastrophe for Hugo. Some of his former friends actually rejoiced in this failure because they resented how successful Hugo was—on all literary fronts.

Still, on opening night, Le Roi s’amuse had brought in more than 3,000 francs—a first-night box office ten times greater than of a typical play—even though a number of free tickets had been given out. Victor Hugo was certainly a name to conjure with.

And Hugo was very responsive to the audience’s reaction. He set out to revise the play in major ways. He wanted to make it more palatable to the public. He wanted to respond to their unwillingness to accept the enormous contrast between the fool whose paternal love rendered him sublime—and the king whose illicit love affairs made him foolish.

Hugo was optimistically revising his play even though the theater director had sent him a note the morning after opening night. The Minister of the interior had ordered Le Roi s’amuse suspended. His reasons? First, what he called the glorification of regicide, and, second, certain unacceptable lines. Primarily, the Minister saw in Triboulet’s attack on the nobles an allusion to the habits of the contemporary royal family. After the nobles insult the jester, Triboulet tells them that their mothers had prostituted themselves to lackeys—as a result, the nobles are bastards. The Minister found this to be an insult to King Louis-Philippe’s mother and grandmother. No matter that the king was François Ier or that Hugo had seriously researched the real court jester before imagining Triboulet.

Hugo immediately counter-attacked, even before the suspension order became a decree forbidding the play. First, he sent a letter to the editor begging “friends of artistic freedom and free ideas to abstain from any supportive violent demonstration, which might end up in the riot that the government seems to have been seeking for so long.” Hugo was already building his case by alluding to the ways in which French monarchies regularly repressed people’s rights bit by bit.

Then Hugo rushed his play into publication. 2000 copies appeared in early December. Hugo used his preface—as he had with other works—to argue for artistic freedom and independence. In this preface, he also prepared his legal attack. He summarized his grievances, answered his detractors, wrote ironically about the cowardice of the Théâtre-Français, and argued that the accusations of immorality were unfounded.

Given the government’s power, Hugo’s case was obviously a lost cause. But Hugo never did abandon what other people found to be “lost causes.” Not only did he hire a well-known attorney—he decided to speak in court himself. Since it was impossible to attack the government directly, they would make the case that the theater had broken Hugo’s contract and thus owed him damages and interest in the amount of 25,000 francs.

Hugo was probably wondering, though: He’d had plenty of experience reading his work to groups of friends, but would he be an effective orator?

The trial:

The trial took place the next afternoon in the impressive Brongniart Palace. If you know Paris, that was the longtime home of the Paris stock exchange—la Bourse—in the elegant second arrondissement. The immense room could not contain all the spectators, and the trial was in many ways a theatrical piece itself. The attorney’s arguments were often interrupted by applause, by shouts, by invective, by laughter—even by people fainting. They had to suspend the session and remove some of the observers.

Hugo’s attorney gave a brilliant speech, connecting the fight that he and Hugo had undertaken with the successful, three-day July Revolution two years earlier. Those battles, he noted, had led to the Charter of 1830, which had abolished theatrical censorship—all censorship, in fact.

Then Hugo took the floor and took a more radical position. In a lofty and literary—yet vigorous—tone, he condemned the government for its pettiness. The Emperor Bonaparte, he said, had also wanted despotism over 30 years earlier. But he had taken people’s rights away all at once, rather than filching them one at a time, as this government was doing.

Hugo ended with a powerful assertion, in which he predicted his own exile, which would indeed come 19 years later: “All it would take would be for this situation to continue just a little while, all it would take would be for the proposed laws to be adopted—and then the confiscation of all our rights would be complete. Today, a censor takes my freedom as a poet; tomorrow, a gendarme will take my liberty as a citizen. Today, they banish me from the theater; tomorrow, they will banish me from the country. Today, they gag me; tomorrow, they will deport me.”

Great applause met Hugo’s final declaration, and the judge called the room to order in a way that Hugo would hear often in the future: “Some members of the public are forgetting that we are not at a theatrical show.”

Although Hugo did not get what he wanted out of the six-hour trial—in the end, the court declined to rule in the case—Hugo did discover that he was a fine orator, a talent that would hold him in good stead in the political career he would embark on a decade later. He also had the satisfaction of rejecting the 2,000-franc annual subvention offered by King Louis-Philippe’s government.

So Le Roi s’amuse was off the stage. But less than two weeks after the trial ended, Hugo’s play about maternal love, Lucrèce Borgia—Lucretia Borgia—went into rehearsals, which Hugo closely oversaw. He had learned from the wobbly rehearsals of Le Roi s’amuse. This new play was a great success.

And in his preface to Lucrèce Borgia, Hugo made the point that the government could not suppress his artistic freedom: “Bringing the public a new drama six weeks after the outlawed drama is the author’s way of showing the government that it’s wasting its time. It’s the way to prove that art and liberty can sprout up again overnight from under the clumsy foot that crushed them.”

Twenty-five years later:

Twenty-five years after the prohibition of Le Roi s’amuse from the French stage, the Paris Théâtre-Italien brought Verdi’s Rigoletto to town. That theater director refused to acknowledge Hugo’s authorship of the original work, or to give him any royalties—just as he had done when staging the Italian operas made from Hugo’s Hernani and from his Lucrèce Borgia.

But Rigoletto was Le Roi s’amuse. Verdi had insisted on sticking close to Hugo’s story, even though he and librettist Francesco Maria Piave had changed some characters’ social status in order to escape scandal and censorship. Hugo’s king became a duke, for instance.

Still, the plot and characters are Hugo’s. Verdi and Piave even used Hugo as inspiration for the famous “La donna é mobile”—“Woman is fickle.” The first two lines of the song come directly from a song in the fourth act of Le Roi s’amuse. Hugo noted that he had seen those words engraved by King François Ier in his Chambord chateau. And the idea that women are as changeable as feathers in the wind was Hugo’s (even though he might well have read it in Vergil first).

So Hugo’s sense of justice was provoked, and his loss of earnings was substantial. With Verdi’s support—he had just lost his own legal battle against that same theater director—Hugo went to court again. But he was in exile on the Channel Island of Guernsey, and the antagonistic government of Napoleon III declared that the opera would be staged “by their order.” That governmental decree left Hugo with no legal leg to stand on.

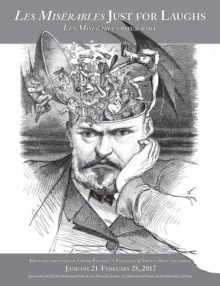

Yet Victor Hugo’s story lives on in the often-performed Rigoletto. And, in Rigoletto, Hugo’s Romantic aesthetic survives. Verdi told how he was drawn to the play precisely because the jester’s grotesquely deformed physicality contrasted with his sublime paternal love. In May 1850, Verdi wrote excitedly: “Oh, Le Roi s’amuse is the greatest subject and perhaps the greatest drama of modern times. Triboulet is a creation worthy of Shakespeare!!!”

So what shocked old-fashioned audience members at Hugo’s opening night in 1832 has entertained the rest of us for over 160 years. Maybe Hugo won his case after all.

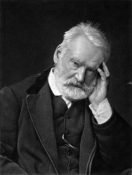

One might argue, as slate.fr has, that Victor Hugo is Paris. A great Romantic poet, world-renowned novelist and fighter for social justice, Victor Hugo dominated nineteenth-century Paris. Students taking this BIS-affiliated J-Term course, “Victor Hugo’s Paris” will explore the City of Light from literary, historical, artistic, biographical and cultural perspectives. Even as you consider the impact Hugo and Paris had on each other, you will analyze how both Paris and Hugo’s ideas are affecting you.

One might argue, as slate.fr has, that Victor Hugo is Paris. A great Romantic poet, world-renowned novelist and fighter for social justice, Victor Hugo dominated nineteenth-century Paris. Students taking this BIS-affiliated J-Term course, “Victor Hugo’s Paris” will explore the City of Light from literary, historical, artistic, biographical and cultural perspectives. Even as you consider the impact Hugo and Paris had on each other, you will analyze how both Paris and Hugo’s ideas are affecting you.